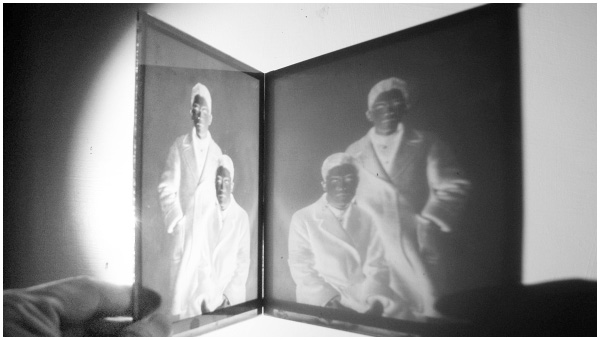

| 高重黎的幻燈簡報電影如同蘊含技術的美學寓意,以殖民論述為後盾,體現他對於機器影像中資本主義本體之嚴正批判,不同於過往以內藏卡式錄音機的幻燈機放映的形式,高重黎刻意選用數位投影呈現〈幻燈簡報電影之七 延遲的刺點—堤II〉,試圖強調攝影、電影與錄像之間的不同,進而探討時間技術性這個至關重要的問題。作品名稱本身暗示藝術家援引羅蘭・巴特的《明室》(1980)一書,以及克里斯・馬克之電影〈堤〉,從中鍛煉自身的史學方法辯證。高重黎以乘載著戰前日本民眾日常景象,象徵常民影像記憶的濕版火棉膠攝影術之負片為視覺論述重心,透過穿插剪輯馬克的〈堤〉,與木下惠介的反戰名作〈二十四隻眼睛〉(1954)中電影場景劇照,以口白驅動影像,重申我們因遭到電影機制綁架,而失去情感的能動性;藝術家撰寫的字卡,則參照馬克思的《路易‧波拿巴的霧月十八日》,進一步論述殖民主義之全球擴張、電影影像之氾濫,以及階級鬥爭之失敗,三者間弔詭的相似性。如同高重黎在影片中所闡釋:「負像是—影像的影像,技術的技術,時間的時間。」高重黎以影像中具有政治性的物質性,與影像中人類社會的歷史,揭示當代的生存境況,以及深陷於機械式感知化約的時間,由動態影像再現、關於歷史軌跡的敘事;換言之,在高重黎的影像論述中,由機器影像/影像機器所操作的影像,早已化為我們當代共享的新型態生命治理技術。 |

As an aesthetic trope of visual technique, Chung-Li KAO’s slide-briefing film embodies his philosophical critique of the capitalistic ontology of mechanical image with the colonial discourse as the backbone. Instead of screening on sound slide projectors (with audio cassettes) as usual, KAO deliberately screens the Slide-Briefing Film No.7— Belated punctum: La Jetée II in the format of digital video to indicate the essential difference, in terms of technicity of time, between photography, cinema, and video. The title of the work suggests points of references on the dialectic of historiography proposed by Roland BARTHES in the book titled Camera Lucida (1980) and by Chris MARKER is the film titled La Jetée (1962). Through highlighting the negatives produced by the collodion wet plate process, which were taken by anonymous Japanese citizens before World War II, KAO re-edits a sequence of stills from both Marker’s La Jetée and Japanese director Keisuke KINOSHITA’s famous anti-war film Twenty-Four Eyes (1954). KAO ‘s voice-over mobilizes these still image to accentuate our collective unconsciousness regarding the exploitation of our sensorial agencies through the cinematic apparatus. The intertitles, also written by the artist, which make direct reference to Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon and others, further theocratize the uncanny parallel between the global expansion of colonialism, the pervasiveness of cinematic image, and the failures of class struggle. In KAO’s words, “the negative is an image of an image, technology of technology, time of time.” KAO draws upon the politic materiality of image and its societal history to show us how much our contemporary living experiences and the narrative of historical traces have been trapped within the mechanical sense of time represented by the moving image of cinema. In other words, for KAO, Image employed by cinema has become a form of governance in our shared contemporaneity. |